Table of Contents

Types of Millets:

This blog will introduce you to the nine primary types of millets cultivated in India. Millets find their place in every state in India, with their distribution depending on factors such as rainfall and growing conditions. They thrive in hilly regions that provide a natural ecosystem, making them a favoured crop in these areas.

Major and Minor Millets:

Millets are categorized based on their prominence and the size of their grains. In terms of significance, they are divided into major and minor millets. The major millets include Sorghum, Pearl Millet, and Finger Millet, which collectively account for 90-95% of the total millet cultivation area. The remaining millets fall under the category of minor millets, which comprises Little Millet, Foxtail Millet, Barnyard Millet, Kodo Millet, Proso Millet, and Browntop Millet.

Husked and Naked Grains:

Millets are further categorized based on the presence or absence of the husk layer. Sorghum, Pearl Millet, and Finger Millets fall under the category of naked grains, while the other millets have husk-on grains. Husked grains require processing to remove the husk for human consumption.

Exploring the Types of Millets:

Let’s briefly delve into each type of millet. A comprehensive understanding of these grains will aid in promoting awareness among people and harnessing their full potential.

Related Post: Importance of Millets in India in today’s scenario

1. Pearl Millet:

Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) is one of the most widely cultivated millets globally. Originating in Western Africa around 4500 BC. It is a significant cereal crop and ranks sixth in terms of both area under cultivation and production. This versatile grain boasts the highest drought tolerance potential among all millets and plays a pivotal role in India’s agricultural landscape. It is the most extensively cultivated cereal in India, following closely behind rice and wheat.

Pearl Millet is cultivated in 36 countries in Africa, though India is the largest country in terms of area (31.5%) and production (46.7%). The average yield level of India is 1237 kg/ha higher than the world average of 834 kg/ha. The states of Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana are at the forefront of pearl millet cultivation, collectively accounting for more than 90% of the country’s pearl millet acreage.

Pearl Millet showcases remarkable adaptability by offering an economical grain yield of 600-700 kg/ha even under marginal and low management conditions. Furthermore, when hybrids with 80-85 days of maturity are grown during the summer season under irrigated and high-fertility conditions, Pearl Millet exhibits the potential to yield a substantial 4-5 tonnes per hectare.

Characterized by its towering, erect stature, Pearl Millet plants can reach heights ranging from 6 to 15 feet. The plant produces an inflorescence featuring a dense spike-like panicle, typically adorned in brownish hues.

Rich in essential compounds such as protein, fibre, phosphorus, magnesium, and iron, Pearl Millet, commonly known as “Bajra” in India, boasts exceptional nutritional value. Its mineral-rich and protein-laden composition endows pearl millet with a multitude of health benefits, making it a vital component in promoting overall well-being.

Pearl Millet supports the livelihoods of approximately 90 million people.

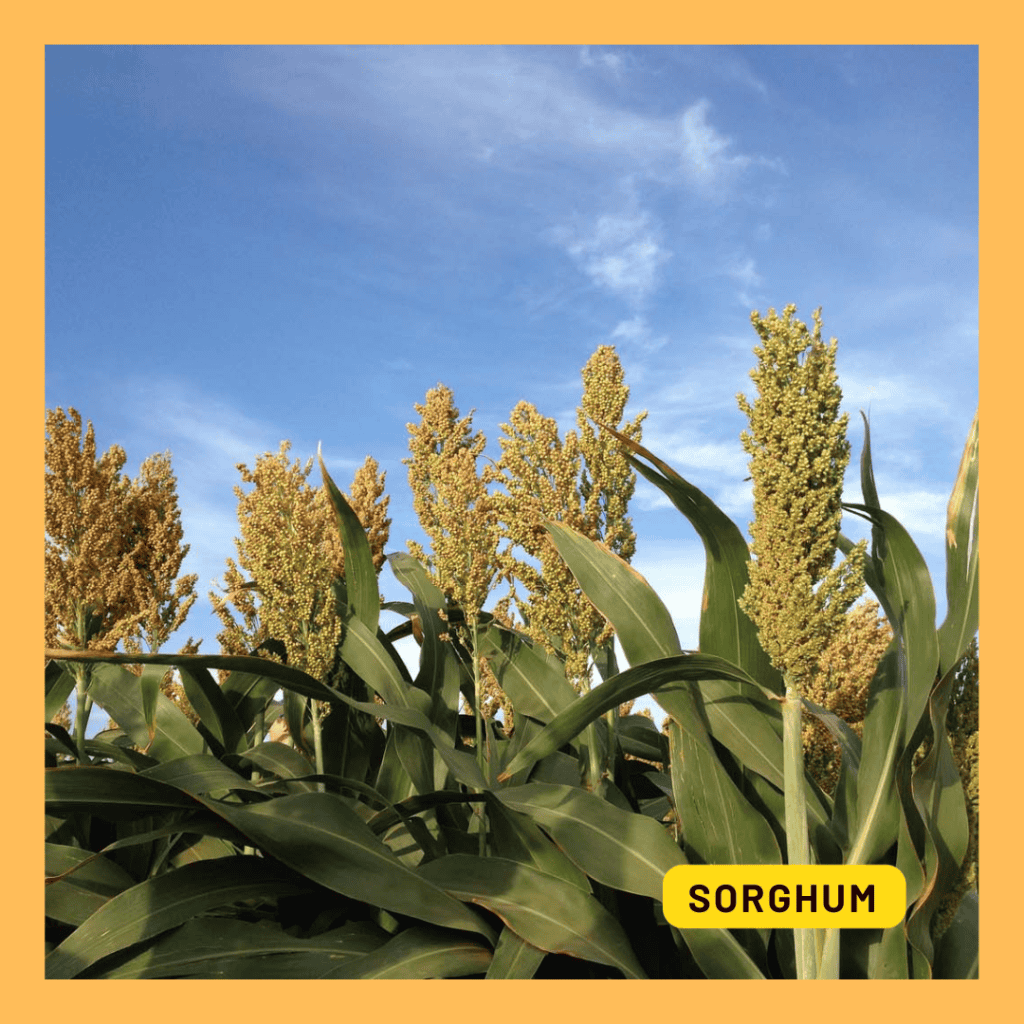

2. Sorghum:

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) finds its origins in northeastern Africa, domesticated between 5000-8000 years ago. Sorghum, also known as Jowar, ranks as the world’s fifth major cereal food crop, both in terms of production and acreage, following rice, wheat, maize, and barley. In India, sorghum grains predominantly serve as a staple food source, while the stover, the residual plant material left after grain harvest, holds significant value as nutritious fodder for livestock. Sorghum’s applications extend to poultry feed and various industrial uses, including the production of potable alcohol.

Scientifically classified as a C4 plant, sorghum stands out as one of the most energy-efficient crops, harnessing solar energy and water resources to produce food and biomass. Its innate drought tolerance enables cultivation across a wide spectrum of environmental conditions. In semi-arid regions, sorghum assumes the role of a dual-purpose crop, with its grains and stover being highly prized for human and animal consumption, respectively.

Certain sorghum varieties are exclusively cultivated to meet the nutritional requirements of livestock, particularly in North Indian states, enjoying prominence as a preferred fodder crop over other cereal options. In India, sorghum cultivation spans across northwestern, western, and central regions, the southern peninsula, and pockets in northeastern states. Maharashtra and Karnataka claim the maximum acreage devoted to sorghum cultivation.

Sorghum distinguishes itself with its robust, tall stems, which can reach heights of 2 to 8 feet and, at times, even soar to a towering 15 feet. Some sorghum varieties feature juicy and sweet stems, akin to sugarcane, and are increasingly gaining attention for bioethanol production. The leaves are approximately 2.5 feet in length and 5 cm in breadth. The petite flowers develop in panicles, ranging from loosely spaced to densely packed; each cluster bearing between 800 and 3,000 kernels.

The seeds exhibit considerable variation across different types, with differences in colour, shape, and size. Based on its diverse applications, sorghum is categorized into grain sorghums, forage sorghums (for use as pasture and hay), sweet sorghums (for syrups and biofuel production), and Broomcorn.

This C4 plant efficiently utilizes solar energy and water to produce biomass and food, ranking fifth globally in cereal production and fourth in India.

A staple source of protein, vitamins, energy, and minerals in semi-arid regions, Sorghum is often termed a “wonder grain.”

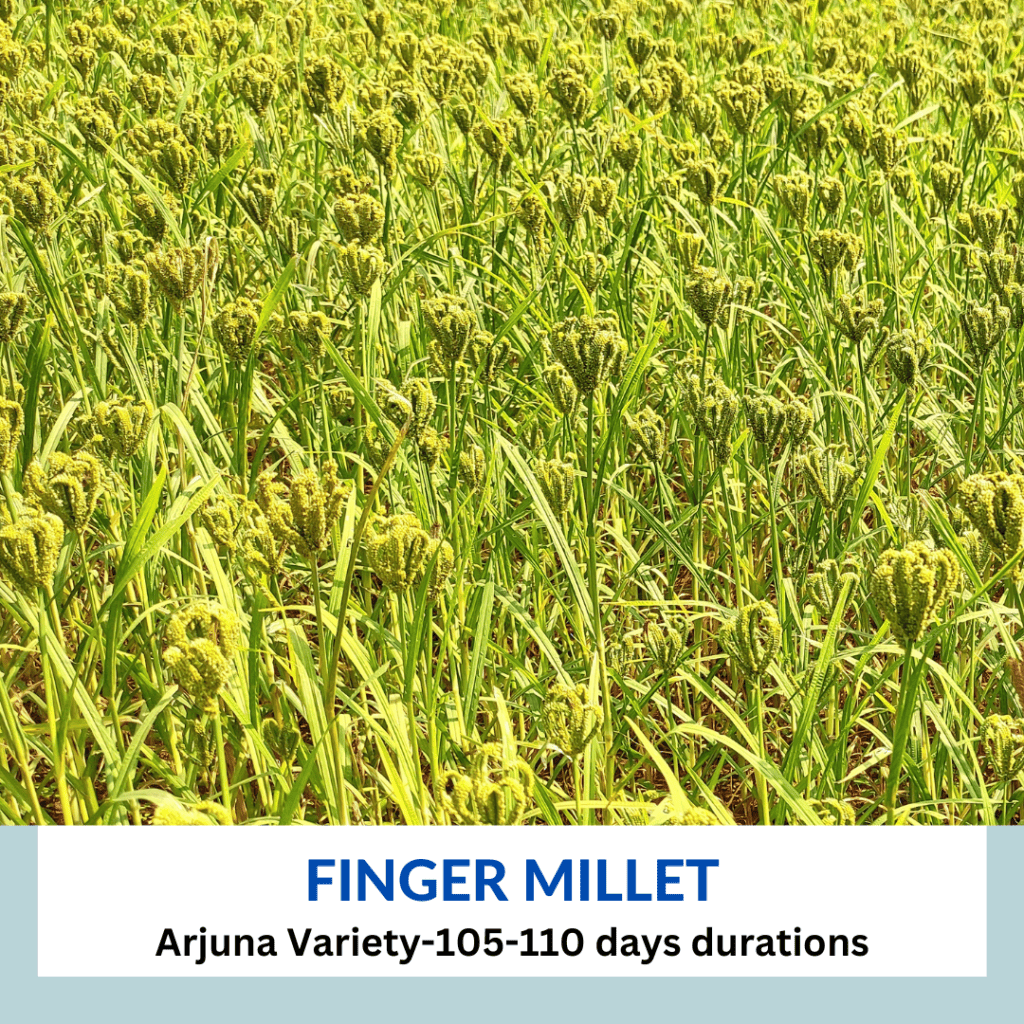

3. Finger Millet:

Finger millet, (Eleusine coracana) also known as “ragi,” holds a crucial role as a primary food source, particularly among rural populations in Southern India and East & Central Africa. With origins in the hills of western Tanzania or the Ethiopian highlands. This resilient crop exhibits a wide range of adaptability, thriving from sea-level regions to the hilly landscapes of the Himalayas, with optimal growth conditions found in well-drained, loamy soils.

Finger Millet is cultivated in 14 countries; the top 5 countries are India, Ethiopia, Nepal, Uganda, and Malawi in terms of area (99.4%) producing 99.6% globally. Ethiopia has the highest yield level of 2301 kg/ha. In India, it is grown in Karnataka, Uttarakhand, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra. Notably, Karnataka is the leading producer of finger millet, contributing to approximately 60% of its global production.

Finger millet is characterized by its dwarf stature and prolific tillering, featuring distinctive finger-like terminal inflorescences. Mature plants typically range from 30 to 150 cm in height, bearing very small seeds that resemble mustard in size and come in varying hues of light brown, dark brown, or white. The crop’s maturation period spans 3 to 5 months, contingent on the specific variety and prevailing growing conditions.

Noteworthy for its nutritional richness, finger millet grains are abundant in high-quality protein, boasting significant quantities of tryptophan, cystine, and methionine. This adaptable crop exhibits a preference for reliable rainfall patterns and possesses an extensive yet shallow root system. Furthermore, finger millet grains exhibit excellent malting properties.

A distinctive feature of Finger Millet is its comparative resistance to storage insect pests, rendering it a vital food source during periods of scarcity and famine. The grains can be safely stored for extended durations, with minimal loss due to deterioration, for as long as 50 years. This resilience and nutritional richness underscore the enduring importance of Finger Millet in providing sustenance and stability to regions facing food insecurity.

4. Foxtail Millet:

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica), ranking as the third-largest crop among the millets, plays a pivotal role in food production within the semi-arid tropics of Asia, while also serving as a valuable forage crop in regions across Europe, North America, Australia, and North Africa. Domesticated over 8000 years ago in China. It is a predominant crop in China with a production of 2.1 million tonnes from 0.79 million ha area.

Foxtail Millet serves as a staple cereal in arid and semi-arid regions, contributing to the development of Chinese civilization. Foxtail millet, often referred to as Italian millet, exhibits the potential for unrealized grain production, offering a slender and erect, leafy stem with variable heights ranging from 1 to 5 feet.

The seeds of foxtail millet are arranged in a spike-like, compressed panicle, bearing resemblance to the inflorescence of yellow foxtail, green foxtail, or giant foxtail. The grain structure is notably akin to paddy rice, featuring an outer husk that must be removed for utilization. Notably, China reports exceptionally high yields, at times surpassing 11,000 kg per hectare.

Renowned for its drought resistance, Foxtail Millet thrives at higher elevations, reaching up to 600 feet, often sown as an alternate crop alongside Sorghum on black cotton soils during periods of deficient rainfall. Additionally, it demonstrates remarkable adaptability to loamy, alluvial, and clayey soils. While China accounts for the majority of global foxtail millet cultivation, regions such as India, Japan, and Russia also partake in its production. In the United States, Foxtail Millet is primarily cultivated for fodder.

Typically found in semi-arid regions, foxtail millet stands out for its low water requirement, aligning seamlessly with its short growing season. The crop matures within 65-70 days, rendering it a valuable choice for late planting when most other crops are no longer viable. This adaptability and rapid growth cycle make foxtail millet a valuable resource for regions facing challenging agricultural conditions.

5. Little Millet:

Little Millet (Panicum sumatrense), a crop originally domesticated in the Eastern Ghats of India, has historically constituted a significant portion of the diet for tribal communities. Thriving in tribal areas of Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh. Its cultivation gradually extended to regions such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Myanmar. Little millet bears a resemblance to Proso Millet, although it tends to be shorter in stature, features smaller panicles and seeds, and is typically grown on a limited scale, often with minimal care, on less fertile lands.

One of its notable attributes is its rapid maturation, making it resilient in the face of both drought and waterlogging. Little millet exhibits less genetic diversity in global collections compared to its counterparts, with grains that closely resemble those of rice. Its cultivation appears to be primarily confined to India, with limited adoption in other regions.

6. Barnyard Millet:

Barnyard Millet (Echinochloa frumentacea) finds its primary cultivation in regions such as India, China, Japan, and Korea, serving as a valuable source of both food and fodder. In India, it is grown in Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh, among other states.

The Japanese and Indian varieties of this millet exhibit robust growth characteristics and possess remarkable adaptability in terms of soil and moisture requirements. They thrive in various seasons and at higher elevations, although their maturation period typically spans three to four months. Barnyard millet cultivation is particularly well-suited for marginal lands where rice and other crops may not yield favourable results.

This erect plant attains heights of 60 to 130 cm, featuring brownish to purple spikelet. In India, it holds dual significance as both a grain and fodder crop, with a notable presence in the hilly terrains of Uttarakhand. Additionally, it enjoys cultivation in parts of Eastern Asia and Africa, while in the Eastern USA, it has emerged as a valuable forage crop.

7. Proso Millet:

Proso Millet (Panicum miliaceum) also known as common or broom corn millet, is a short-season crop that finds cultivation in arid regions across Asia, Africa, Europe, Australia, and North America. This millet variety is particularly valued for its quick maturation and relatively low moisture requirements, making it an ideal choice for emergency or short-duration irrigated crops. Moreover, Proso millet is notably undemanding, exhibiting resilience against known diseases. Its adaptability extends to a wide range of soil types and climate conditions.

One of its defining attributes is its impressive drought resistance, making it a viable option for regions characterized by low water availability and extended periods without rainfall. Proso millet stands out as a short-season crop, typically reaching maturity within 60 to 75 days after planting. It is frequently grown as a late-seeded summer crop, well-suited to diverse agricultural contexts.

Proso millet plants reach a height of three to four feet, with a distinctive compact panicle that gracefully droops at the top, evoking the image of an old broom—hence its moniker “broom corn.” The millet’s round seeds, measuring about 1/8 inch in width, are encased in a smooth, glossy hull and come in a range of colours, including cream, yellow, orange-red, or brown.

Once hulled, the grain yields a nutritious and palatable cereal, suitable for unleavened bread or cooking. Historically, Proso Millet was cultivated in regions like Russia, China, the Balkan countries, and Northern India. However, it was later replaced in many areas by rice and other cereals, reflecting evolving agricultural preferences over time.

8. Kodo Millet:

Kodo Millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) native to the tropical and sub-tropical regions of South America, was domesticated in India approximately 3,000 years ago. This millet variety exhibits extensive cultivation primarily within India, particularly on soils considered less fertile, where its growth is comparatively limited in other regions. Grown primarily in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, and Odisha.

Kodo millet has gained a reputation for its exceptional hardiness, drought resistance, and capacity to flourish in stony or gravelly soils that may not support other crops. It distinguishes itself with a relatively longer growth duration, typically spanning four to six months for maturation, although shorter-duration varieties have been developed in recent times.

Kodo millet is characterized as an annual tufted grass, reaching heights of up to 90 cm. The grains are encased in hard, corneous, and persistent husks, which pose a challenge to their removal. The grain’s colour may vary, ranging from light red to dark grey. This durable and adaptable crop remains a significant component of agricultural practices in India.

9. Browntop Millet:

Browntop millet, originally native to India, finds its primary cultivation primarily in the regions of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. In the United States, it finds use in the Southeast for hay, pasture, and bird feed. Grown in plantation areas, it is especially popular in the Chitradurga, Tumakuru, and Chikkaballapura districts of Karnataka state.

However, it’s noteworthy that this millet’s presence as a weed is observed across all states in India. While it is primarily utilized as a food crop in India, its versatility extends to thriving in less fertile sandy loam soils, with a relatively short maturation period ranging from 60 to 80 days. It stands out as a cost-effective crop with minimal requirements, eliminating the need for weeding and being notably resistant to pests and diseases.

In the United States, Browntop Millet enjoys annual cultivation spanning as much as 100,000 acres, predominantly in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. Here, it serves the dual purpose of hay production and pasture land, with its seeds providing valuable sustenance for quail, doves, and other game birds. As a fodder crop, it distinguishes itself with finer stems and rapid growth, outpacing Pearl Millet in these aspects.

Conclusion:

Hope, now you have a comprehensive overview of the types of millets cultivated in India. India’s diverse landscape supports the cultivation of various millet types, offering unique nutritional benefits. From Pearl millet to Sorghum, Finger Millet to Foxtail Millet, these ancient grains hold promise for both nutrition and sustainability. Please share this blog with someone who can benefit from exploring the nutritional and ecological advantages of incorporating millets into their diet.

Author: Tapas Chandra Roy, A Certified Farm Advisor on Millets, ‘Promoting Millets from Farm to Plate’ and an Author of the book -” Millet Business Ideas-Empowering Millet Startups”. In a mission to take the forgotten grains- Millets to Millions. To remain updated on my blogs on Millets please subscribe to my newsletter and for any queries please feel free to write to [email protected]